The Danes have actually been to space. First, many Danish companies provided software and equipment to NASA and the European Space Agency, maybe most prominently Christian Rovsing A/S back in the 60s and 70s. In 2015, Andreas Mogensen spent a week in the International Space Station and became the first (and so far only) Danish astronaut. This, of course, was predicted by the hilarious Danish full-length cartoon comedy “Rejsen til Saturn” (Journey to Saturn) from 2008 based on an earlier comic book of the same name.

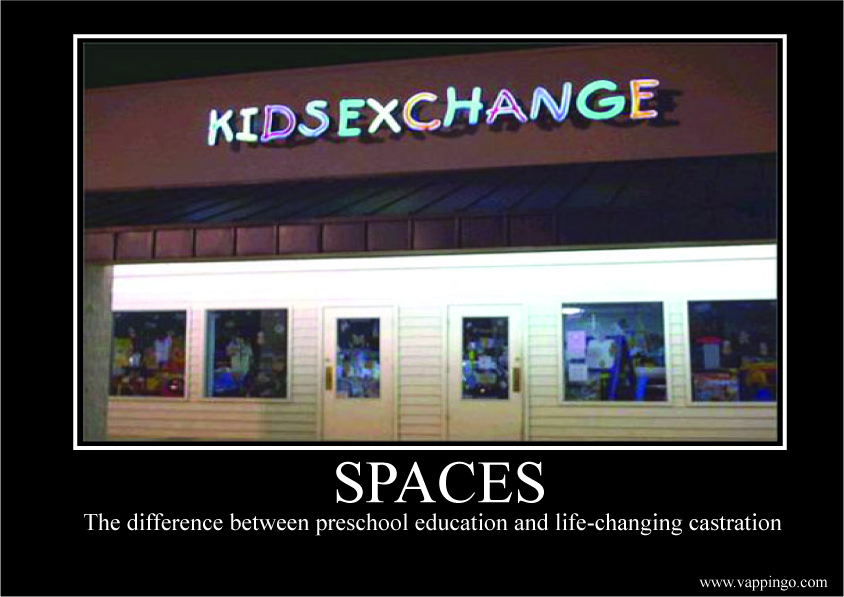

But, of course, this is not the kind of space, we want to talk about here… Our space-challenge at hand is about whether a space should or should not be inserted between two Danish words. The issue has risen in urgency since the invasion of the English language and its handling of two nouns next to each other, where the first noun actually acts as an adjective describing the other noun. Things like “winter shoes” or “work clothes” are two words in English, where in Danish, since they naturally belong together, they become one word: vintersko and arbejdstøj. Like the Americans would say: “some things just belong together, like peanut butter and jelly”, where Danes take the consequence of that and make “peanutbutterandjelly”. Just kidding! -Every Dane knows that jelly goes on cheese and not on peanuts. 🙂

So, writing Danish with some knowledge of English grammar is firstly challenging in regards to whether to separate the words or not (when in doubt, you’re probably right going with a compound word in Danish). The second challenge is purely of Danes’ own making: after you’ve smooshed the two words together, you should also be able to pronounce the resulting word. Yes, some times two words just don’t become one word without putting up a fight. This is typically solved by inserting an extra ‘s’ if, for instance, the first word ends in a vowel and the second word also starts with a vowel. But if the insertion or omission of an ‘s’ produces a new legitimate Danish word , then things get funny. You can produce a brand new word that still has meaning, -just not the meaning you intended.

We caught a few of those one-letter bloopers in a previous posting. Here’s a collection of some further one-letter-off or one-space-too-little golden nuggets:

Danish ==> English

Arbejdstøj ==> work clothes

Arbejdsstøj ==> noise in the workplace

Rygbænke ==> back benches (exercise equipment)

Rygebænke ==> cigarette smoking benches

Flotte nylonstrømper ==> gorgeous nylon stocking

Flotte nylonstrømer ==> a gorgeous policeman made of nylon

Dyreartikler ==> items for animals

Dyre artikler ==> expensive items

Tekstilsalg ==> sale of fabric

Tekst til salg ==> text for sale (like for a blog or an advertising)

Børnepuder ==> pillows for children

Børnepudder ==> baby powder

Billige kvinder frakker ==> cheap women (in) coats [this is not proper Danish, but I’ve seen an ad with this headline]

Billige kvindefrakker ==> cheap coats for women [this was the intended meaning]

Lederuddannelse ==> Leadership education

Læderuddannelse ==> Education in leather

Uddannet ==> educated

Uuddannet ==> uneducated

Udannet ==> showing bad manners

Buskrydder ==> a hedge trimmer [=busk+rydder]

Buskrydder ==> an alcoholic drink (a bitter) enjoyed on the bus [=bus+krydder]

Bærbusk ==> berry bush

Bær busk ==> carry a bush

Forretning ==> business

Forrentning ==> interest on a loan

Fladskærm ==> flat screen

Faldskærm ==> parachute

Skifte tid ==> to change time

Skiftetid ==> shift-hours, duration of a work shift

Skift tidsplan ==> change time schedule (skift is here a verb, so no compounding)

Skiftetidsplan ==> shift-schedule (dash – is there because otherwise ‘shift schedule’ is ambiguous in English)

Slagterpigerne ==> the Butcher Girls

Slagter pigerne ==> (he/she) butchers the girls

Skær sild ==> cut the herring (fish)

Skærsild ==> purgatory

Krabbe klør ==> a crab is itching

Krabbeklør ==> crab claws

And some naughty ones! :):

Sameje ==> joint ownership

Samleje ==> intercourse

Bedstemors boller ==> grandma’s bread rolls

Bedstemorboller ==> grandma’s bread rolls [here the compounding results in REMOVAL of the s]

Bedstemor boller ==> grandma is having sex

Førstegangsydelse ==> First installment (of a loan payment)

Førstegangsnydelse ==> Enjoying the first time

Blære røv ==> bladder (and) ass [human parts]

Blærerøv ==> a boaster, a braggart

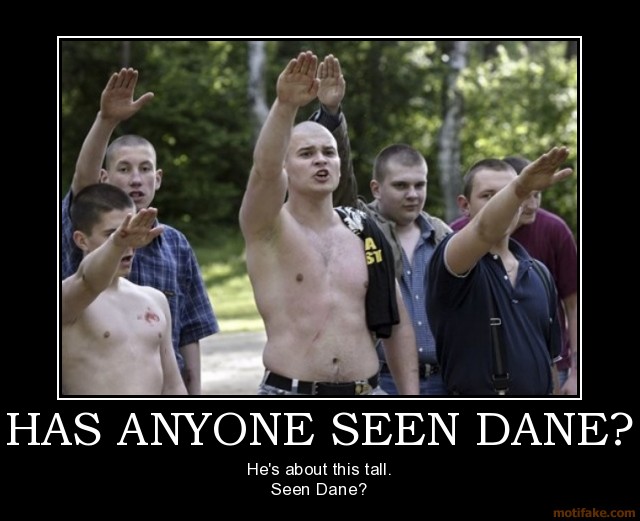

Fællesspisning ==> a community dinner

Fællespisning ==> group pissing

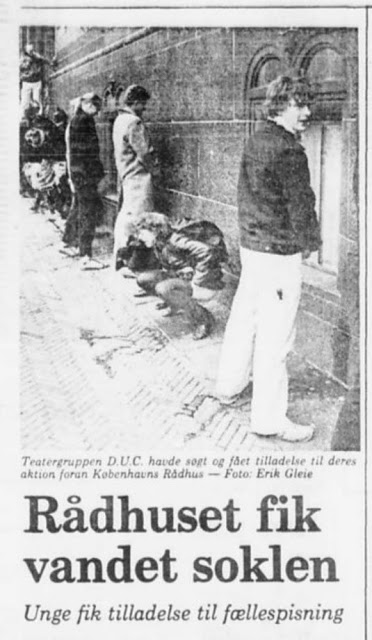

In 1986 a group of performance artists actually on purpose tricked the Copenhagen magistrate to give them a permit for fællespisning, where of course the magistrate believed that they were approving a fællesspisning, as this newspaper clip shows: 🙂